| I UNIT ONE: INTRODUCTION TO CURRENT ISSUES AND CONCEPTS |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Well-Being for All

At the World Summit for Social Development, convened in Copenhagen, Denmark, 6-12 March, 1995, the representatives of 186 States signed the ten commitments included in the “Copenhagen Declaration on Social Development”: “For the first time in history, at the invitation of the United Nations, we gather as heads of State and Government to recognize the significance of social development and well-being for all and to give to these goals the highest priority both now and in the twenty-first century.” a a Report of the World Summit for Social Development, Copenhagen, 6-12 March 1995 (A/CONF.166/9), chap. I, resolution 1, annex I, para. 1. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A. WHY THIS MANUAL? The concept of well-being for all stresses the importance of organizing society so that it can provide opportunity and security to all its members, whatever their circumstances and capacities. Within this framework, the General Assembly, at its forty-sixth session, in 1991, invited “all organizations of the United Nations system to incorporate the needs and concerns of persons with disabilities in their programmes and activities both active agents and beneficiaries”.1 This manual is intended to provide practical guidance on how this can be done. More generally, it addresses the question of how the concept of well-being for all can be put into practice with specific reference to the equalization of opportunities forersons with disabilities, thus ensuring their full integration into society. 1. THE UNITED NATIONS DECADE OF DISABLED PERSONS The international community expressed its concern and commitment to the equalization of opportunities for persons with disabilities in the World Programme of Action concerning Disabled Persons, which was adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1982 by Assembly resolution 37/52.2 Ten years later the General Assembly proclaimed the day on which the World Programme was adopted, 3 December, as the “International Day of Disabled Persons”3. The basic objective of the World Programme of Action concerning Disabled Persons “is to promote effective measures for prevention of disability, rehabilitation and the realization of the goals of ‘full participation’ of disabled persons in social life and development and of ‘equality’. This means opportunities equal to those of he whole population and equal share in the improvement in living conditions resulting from social and economic development. These concepts should apply with the same scope and with the same urgency to all countries, regardless of their level of development.” a a World Programme of Action concerning Disabled Persons, para. 1. The United Nations Decade of Disabled Persons (1983–1992) was proclaimed as the initial time frame for the implementation of the World Programme of Action. The International Year of Disabled Persons 1982 (IYDP) set in motion a process towards awareness of the problems — and potentials — of persons with disabilities. From Objects of Care to Agents of Action The first breakthrough occurred already while the Decade was prepared. The original proposal to have a year FOR disabled persons was amended to a Year OF Disabled Persons. This indicated the beginning of a revolutionary approach to disability issues with the recognition that people with disabilities are, first of all, people who have the ability, the will and the right to be active agents in charge of their own lives. The World Programme of Action, inter alia, strongly urged the organizations within the UN system to “explore, with the Governments to which they are accredited, ways of adding to existing or planned projects in different sectors, components that would respond to the specific needs of disabled persons” (emphasis added).4 In developing countries, intergovernmental, governmental and non-governmental donor agencies have initiated various projects in order to assist persons with disabilities. A piecemeal approach that is built on scattered and isolated projects has, however, very limited and often non-sustainable effect on the lives of persons with disabilities. After all, it is not economically feasible to cater for the needs of all disabled persons through“disability-specific” projects that are targeted to disabled people only. Having realized the limitations of the project approach, some donor agencies have developed a more comprehensive strategy, a systematic programme approach, to guide their activities. A further step in comprehensive development strategies is the “inclusive approach”. It aims at taking into consideration the needs and the otentials of all diverse population groups within a single planning and action framework. There are disabled people in all population groups. The purpose of this Manual is to assist in the planning and design of development policies, programmes and projects that include the disability dimension as a natural element. This would add on social value to the results of development activities usually with minor or no post at all. 2. THE MANDATES In its resolution 42/58 the General Assembly invited Member States to incorporate in their national development plans and strategies projects to assist persons with disabilities and to include such projects in the country programmes of the United Nations Development Programme (emphasis added).5 Furthermore, the Assembly renewed its “invitation to all States to give high priority (emphasis added) to projects concerning the prevention of disabilities, rehabilitation and the equalization of opportunities for disabled persons within the framework of bilateral assistance programmes.6 The General Assembly has since repeatedly requested the Secretary- General, “to encourage all organs and bodies of the United Nations, including regional commissions, international organizations and the specialized agencies, to take into account in their programmes and operational activities the specific needs of disabled persons” (e.g. General Assembly resolutions 42/58, para. 7, 43/98 para. 6, and 44/70 para. 7). Moreover, a United Nations Expert Group Meeting which considered a longterm strategy to further implementation of the World Programme of Action, which was held at Vancouver, Canada, from 25- 29 April 1992, proposed that “disability issues should be integrated into the mainstream activities of intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations”.7 Meeting participants further emphasized the need for integrated disability policies at all levels8 and that national plans should include “specific measures for the integration of disabled persons into mainstream society and the consequent integration of disability issues into the planning process of all sectors” (emphasis added).9 The forty-seventh session of the General Assembly, having taken note of the report of the Secretary-General on the monitoring of the implementation of the World Programme of Action concerning Disabled Persons,10 urged Governments to show their commitment to improving the situation of persons with disabilities, interalia, by “addressing disability issues within integrated social development policies linked to other socio-economic issues, with the ultimate objective of facilitating the full integration of persons with disabilities in society”, and “integrating, where possible, disability components in technical assistance and technical cooperation programmes”.11 The same resolution requested the Secretary-General, inter alia, to “integrate disability issues in policies, programmes and projects of the specialized agencies of the United Nations on a broader scale and with a higher priority”. 3. DISABLED PEOPLE AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT Development for All “The ultimate goal of social development is to improve and enhance the quality of life of all people. It requires democratic institutions, respect for all human rights and fundamental freedoms, increased and equal economic opportunities, the rule of law, promotion of respect for cultural diversity and rights of persons belonging to minorities and an active involvement of the civil society. Empowerment and participation are essential for democracy, harmony and social development. All members of society should have the opportunity and be able to exercise the right and responsibility to take an active part in the affairs of the community in which they live.” a Report of the World Summit for Social Development, Copenhagen, 6-12 March 1995 (A/CONF.166/9), chap. I, resolution 1, annex II, para. 7. Development efforts aiming at sustainable social development should enhance the potential of all people to participate in development. Development efforts should, therefore, focus particularly on the empowering of poor and marginalized people to participate in and contribute to mainstream activities in the social, economic, cultural and political arenas of life. This is done through supporting activities that enable the poor and marginalized people to gain better command of their lives:

However, in practice development efforts often fail to recognize the rights, needs and potentials of those people who are the most marginalized. Consequently, while people with disabilities are often among the poorest of the poor, they have been excluded from mainstream development activities.12 Do not use a spoon to try to empty a river For instance, poverty is a multidimensional and often intergenerational process characterized by a continuous lack of access to: • Political, social, cultural, juridical and economic institutions, • Productive resources, goods and social services, • Information and education, • Safety and human security, • The built environment, etc. The structural obstacles to participation and the perpetuating exclusion processes cannot be changed with ad hoc piecemeal projects.a a Report of the World Summit for Social Development, Copenhagen, 6-12 March 1995 (A/CONF.166/9), chap. I, resolution 1, annex II, para. 19. See also, innish National Committee of the International Council on Social Welfare, “The Tampere Declaration of the Global Welfare ’94 Conference”; 26th World Conference of ICSW (Helsinki, October 1994). People with disabilities are at high risk of being systematically denied their access to the resources needed for the full exercising of their human rights. In all ocieties, children and women with disabilities are particularly vulnerable in this respect. In some societies, children with disabilities are totally excluded from society as they are condemned, often right after birth, to spend their childhood and youth in institutions for disabled children.13 4. FOR WHOM HAS THE MANUAL BEEN DESIGNED? Despite the frequently expressed concern by the international community, the rights and needs of people with disabilities have in most cases been inadequately dealt with in development co-operation. The reasons have hardly been economic in nature. Rather there has been lack of awareness. Another reason for omitting isability issues in development projects has been the lack of practical guidelines and functioning procedures on how to deal with the issue in project planning, appraisal and implementation. The Manual is designed to serve as a tool for translating into good practice the principles of development from the social perspective, which have been agreed upon by the international community. By incorporating the disability dimension in daily practice of policy making, planning and decision making, it should be possible to ensure a favorable environment for people with disabilities to participate in and contribute to the development of the societies in which they live. The manual is aimed at assisting national senior policy makers, planners, administrators, personnel of international development assistance agencies as well as private philanthropic foundations to add to the social value of their activities. In particular, the manual is directed to those who are involved in mainstream policies, programmes and projects which are designed to benefit the entire population. A second objective of the manual is to further the inclusion and the full participation of persons with disabilities and their organizations in planning workshops and task forces. In general, the manual aims to promote improved understanding and expanded partnership between mainstream development planners and people with disabilities. Therefore, the manual provides introductions to current disability concepts and concerns to those who are experts in planning, and, on the other hand, provides an introduction to basic planning concepts and methods to those stake holders who may not be familiar with these issues. 5. WHEN SHOULD THE MANUAL BE APPLIED? For development efforts to achieve the highest feasible quality of results, their impacts on concerned population groups need to be taken into account in a balanced way. All people are equal — they should be “The principle of equal rights for the disabled and non-disabled implies that the needs of each and every individual are of equal importance, that these needs must be made the basis for the planning of societies, and that all resources must be employed in such a way as to ensure, for every individual, equal opportunity for participation.”a The fundamental needs of persons who have disabilities are the same as those of non-disabled people. However, persons with disabilities often may encounter obstacles while trying to participate in mainstream society which has been designed with non-disabled people in mind. Many barriers are unnecessary and can be avoided simply by exercising forethought at the planning stage already. CHECKPOINT 1 Are you planning activities that may be relevant from the disability perspective? Checklist 1: Does the planned development activity contain one or more of the following elements?

If a development activity includes one or more of the above elements, then the activity is relevant from the perspective of persons with disabilities.

|

Codes

- = Not Desirable

+/- = Acceptable in Selected Cases

+ = Viable Option

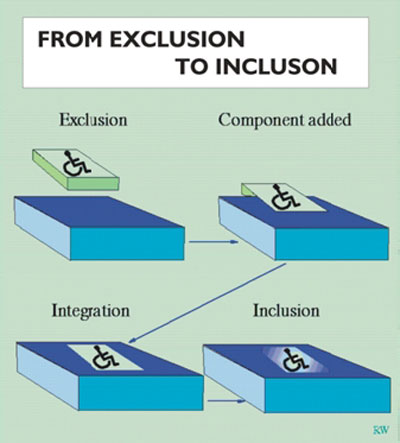

| added to a mainstream activity; for instance, community-based rehabilitation projects may be introduced into health care development programmes as components with separate administration, staff, and facilities. The intermediate stop is the “integrated approach”. This would involve design and planning of services and facilities that respond to particular needs of disabled persons. They are placed within mainstream programmes and budgets but are destined for disabled persons only. An example could be the introduction of special classes for disabled pupils in the mainstream schooling environment and under the same educational administration. FIGURE I. 2: THE EVOLUTION OF APPROACHES TO DISABILTY

(c) “Inclusive approach”. The disability dimension is flexibly included in all aspects and stages of an activity as a central element. This approach requires maximum integration throughout the planning and programming process and appropriate adaptation of mainstream facilities and services so that they can adequately serve both persons with disabilities and non-disabled people. It also implies full and effective involvement of persons with disabilities as equal partners in the planning and running of an operation. A specific support service component may sometimes be needed to empower disabled people. For instance a pupil who is deaf can follow the same curriculum in the same classroom as his/her peers with the help of a Sign Language interpreter and/or appropriate technical aids. While striving towards full integration and ultimately inclusion, the inclusive approach should not be pursued until mainstream development is able to generate and maintain the essential support services that persons with disabilities may need for full and effective participation. Each approach can, in principle, be applied at any activity levels, i.e. while establishing conceptual foundations, at policy design, programme or project planning levels as well as during actual operations and monitoring exercises. However, in the light of the principles discussed in the preceding paragraphs, all development activities should at least adopt an inclusive conceptual framework, inclusive value statements and objectives regarding disability issues. The alternative is a conceptualization in which persons with disabilities are considered to be different from other members of society to the extent that particular theories and concepts would be needed. Unfortunately, such conceptualizations exist and they often are applied. Concepts are tools to produce thoughts and plans; there are good tools and bad. Theoretical frameworks or political ideologies based on the devaluation of specific human characteristics, one-dimensional classifications or simplistic diagnostic frameworks, labelling concepts, value loaded, biased and discriminating language, aims and options that segregate against specific groups of people on the basis of characteristics related to the person and his/her identity are common but in obvious conflict with the policies and principles adopted by the international community. An example of a less obvious trap is the “human capital” approach. It may be interpreted so as to lead to the commodification of humanity, seeing a person as being worth what she or he can produce. Consequently, people with disabilities will not be in the focus of public expenditure. The human capital approach could, for instance, be replaced with the wider terms of “human resources” or “human capabilities” development.a a United Nations, “Report of the consultative expert meeting on integration of disability issues in development cooperation activities (Vienna, 29 May – 2 June 1995)”. The conceptual starting point of any development activity should be full participation on the basis of equality of disabled people in society. In practice, persons with disabilities are often segregated and disadvantaged to the extent that their concerns require additional and specific action. Should it not be immediately possible to cover all disability issues within an inclusive policy framework, a specific disability programme component needs to be introduced into the national development policy. Incorporating a disability dimension in all activities of the social and health sectors The Government of Finland Programme for “Supporting the reconstruction of the health and social sectors of the Republic of Karelia of the Russian Federation” includes the following priority areas that have been agreed with the Karelian authorities: (1) Development of primary health care, (2) Development of social security and services, (3) Human resources development, (4) Development of management and planning capacities, (5) Coordination of international support .For instance, component number 2 includes a specific sub-component on “disability services” to launch a focused process that would lead to identification of alternatives to institutional approaches to services delivery and to the design of alternative institutional arrangements. To make such developments possible, relevant disability issues must be incorporated in all other relevant programme components as well. For instance, in component number 3, “human resources development”, the disability dimension will be integrated in curriculum development.a a STAKES/Hedec, “Support for implementation of social and health care reforms in the Republic of Karelia, Russian Federation 1995- 2000”; project document (Helsinki, 1995). In some cases, equalization of opportunities for disabled persons requires a specific disability programme at the first stage of development. At both the project design and the operational levels, a component approach – and even a disability-specific design of operations which take into account the needs, rights and potentials of disabled persons – may sometimes be the best way to achieve full inclusion of persons with disabilities in the long run. A focused investment in persons with disabilities may be the first step towards their empowerment According to a report on the experience of Namibia, at the initial stages in the design of new disability policy, emphasis will be accorded to the disability-specific approach to promote empowerment of various disability groups. With time, consideration will be given to general approaches to policy design that call for inclusion of nondisabled persons as well.a a Hadino Hishongwa, “Namibia: integration of disability issues in development cooperation activities”, note contributed to United Nations Consultative expert meeting on integration of disability issues in development cooperation activities (Vienna, 29 May – 2 June 1995). Caution must, however, be exercised so that the disability-specific approach does not become the only and final solution

1. THE MULTI-DIMENSIONAL CONCEPT OF DISABILITY 14

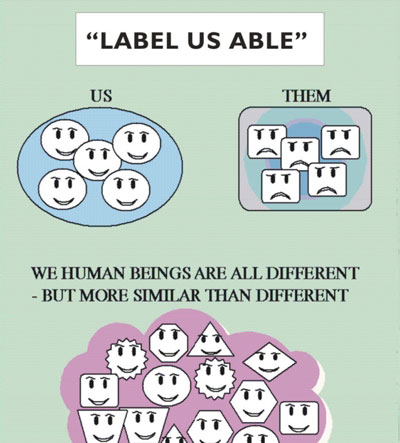

“Disability” should not be viewed in terms of a dichotomy of ability or disability. Instead, it should be seen in terms of an ability-disability continuum. For legal purposes, such as defining disability for the purpose of measuring eligibility for a specific entitlement, it is necessary to decide on a cutting point beyond which ability is considered “disability”. For statistical purposes, it is necessary to classify people according to mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories. Even then there is wide variation in the degree and type of ability within such categories. It has been estimated that, on average, some 5–10 per cent of the population have some form of a disability. This period ratio (prevalence ratio) is, however, misleading if it is interpreted to indicate the proportion of people experiencing disability in their own life. The cumulative incidence rate over the whole life cycle of people is much higher. People should not be labelled on the basis of one characteristic. Terms such as “invalid” or “the disabled” reinforce stereotyping that artificially divides people into “them” and “us”. Strictly speaking, a person whose legs have been amputated is not “disabled” but is more correctly described as a person with a disability. The fact that he or she has to move around using techniques other than those used by people with two functioning legs does not imply that the person is any less able to do everything else as easily and as well as people who walk. The fact that this is not always the case is a consequence of the lack of opportunity to acquire and develop the necessary skills – not the lack of ability.

There are no absolute criteria for defining disability. Concepts and definitions are a matter of convention and convenience. The latest definitions are included in the United Nations Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities:18

Assistive devices, adaptation of work and housing environments, preparation of the family and community to meet the person with disabilities, and sometimes personal assistance need to be added on a case-by-case basis to obtain the full value of rehabilitation efforts.

Mines – meaningless for war but disastrous for children “During the past decade, more than 1.5 million children have been killed by wars and armed conflicts, over 4 million were permanently disabled. An estimated 10 million children are victims of psychological trauma. One in every 230 Cambodians is an amputee due to land mines, which continue to claim about 300 victims a month. A land mine can be manufactured for as little as US$3, the cost of clearing a single mine ranges from US$300 to US$1,000, which is higher than most people’s annual income in developing countries.”a a United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Anti-personnel mines: a scourge on children (New York, 1994). As wars and armed conflicts are one of the major causes – both directly and indirectly – of mental and physical trauma and disablement, international cooperation in all forms should include objectives and components that are aimed at preventing violence through promotion of human security and combatting of prejudice, misuse of power and segregation in all forms. A particular responsibility of Government is to object strongly to the use of arms which aimed bluntly at disabling civil populations, particularly children. 5. FROM LABELLING TO ENABLING There are many conceptual frameworks for development analysis and planning. However, not all are necessarily consistent with current approaches that (a) put people in the centre of development as beneficiaries and agents of change, (b) recognize the significance of social development and human well-being for all and (c) give “to these goals the highest priority both now and into the twenty-first century”.27 The above approach endorsed by the international community at Copenhagen is based on the recent revolution in human sciences. Rather than see people as passive objects under the influence of external causes, emphasis is directed to the active and purpose-oriented nature of all human beings. The fundamental purpose of a person is not to satisfy the survival needs only, but to live a meaningful life. All aid is not development aid “A basic needs” approach, if focusing only on survival needs, chains people as objects of charity for their life. Long-term “feeding” of a community has a tendency to destroy productive potentials and local market structures. Emergency aid should, as appropriate, be of necessities accompanied by interventions which build capacities for sustainable local production. Similarly, charity and care-taking that replace activities that people normally would do themselves can diminish people’s basic aspirations – and eventually otivation – to seek actively viable solutions themselves. People want to – and can – be agents of their own lives. To live a meaningful life, one must have some degree of command over the course of one’s life. To gain such command, one must have certain prerequisites for coping with various aspects of life in a goal-oriented manner. Certain of the prerequisites are provided by the environment in which one lives; certain pertain to personal capacities.28 FIGURE I.4: PREREQUISITES FOR COPING 29

People can overcome coping problems in a number of ways, which include: changing or adapting physical, social or cultural environments, acquiring morefunctional knowledge, learning new functional skills, increasing motivation, or improving health. The enablement approach recognizes the multi-dimensional potential and capacities of people themselves. People should not be classified on the basis of one characteristic into “us” and “them”. People with disabilities are people first. Disability is only a secondary dimension. Their aspirations, needs, rights and problems are best addressed through an enabling approach that is applicable to all people. Enabling all people to use their own potential and to take responsibility contributes to a sustained and equitable process of development.

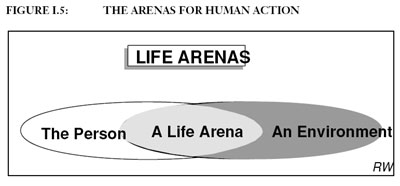

“For too long, persons with disabilities have been isolated, their right to development ignored, and their potential contribution to society neglected. The old attitude regarded disabled people as dependent invalids, in need of protection. It understood disability as a stigma, allowing society to send a person with disabilities to the appropriate address in the social structure, which, unfortunately, too often was the address of a special institution. But times are changing. The proclamation of the international Year of Disabled Persons in 1981 and the United Nations Decade of Disabled Persons (1983-1992) heralded a major shift in attitudes toward disability. The new approach stresses abilities, not disabilities, it promotes disabled people’s rights, freedom of choice and equal opportunities; it seeks to adapt the environment to the needs of persons with disabilities, not the other way round. It encourages society to enhance its ttitudes towards persons with disabilities and assist them in assuming full responsibility as active members of society.”30 Society is a construction of people themselves. It gains its legitimacy by its ability to ensure the realization of human rights for all. “A society for all” will also be fit for us when we grow old “We human beings are all different. We have different needs, and different qualifications, different strengths and different weaknesses. Therefore, the society in which we live should never be formed on the basis of special demands by the few. The society must be formed in such a way that it will suit all. The needs of disabled persons must influence the planning of our societies as much as the needs of nondisabled persons, not because we must pay special attention to the disabled, but because they are citizens of the society as everyone else. Therefore, their needs must be included in the building of the society as a matter of course. This concept favours us, the non-disabled, partly because the needs of disabled people are the same as for many other groups and partly because we and our relatives through illness or accident may one day belong to the group of disabled persons ourselves. And then, we would, of course, wish that our daily life, i.e. our jobs, our homes, our social relations, our leisure time activities, as far as possible will continue as before. We do not wish that practical defects in planning of the society shall force us to limitations and changes which the disability itself does not make necessary”.a a Olof Palme, late Prime Minister of Sweden, cited in Bengt Lindqvist, “A society for all; on disability policy”, The World Blind, nos. 7 and 8 (1992). 1. PLANNING FOR ALL Detailed planning seldom is possible because societies and communities are constantly evolving processes. Rather, planning should be focused on creating favourable environments for people’s constructive activities. To develop societies that enable people to fulfil their potential, it is necessary to adopt more proactive approaches: to acknowledge people’s abilities and interests and to support them in achieving full participation and self-determination. First of all, the focus should shift from disabilities to abilities. There currently are (1997) some 5.6 billion different people in the world. Some have a difference called disability. Planning for the average person serves a minority only, because there are only a few people who can be considered average. Between 20 to as many as 50 per cent of national populations are comprised of children under age 15; and about 50 per cent of all adult populations are omprised of women. What should then the planner’s “average” person be? Planning for specific groups leads to impossibilities because the number of possible specific groups is infinite. Flexible planning for different people serves all, because people are different. People are more similar than different While allowing for flexibility, plans must first focus on the fundamental similarities of people. All people are engaged in interaction with their environments in several “life arenas” to fill their needs and to fulfil their aspirations. FIGURE I.5: THE ARENAS FOR HUMAN ACTION  “Life arenas” include people’s interactions between the man-made and natural physical environments, and between economic, social, cultural and communication systems. “A society for all people” aims to ensure equal opportunities for all people to derive their well-being from these life arenas. Therefore, the diversity of people and potential obstacles to their full participation in various life arenas should be taken into account at the planning stage. From the planner’s perspective, questions to be asked include the following: (1) What are the basic activities in which all people are involved on a daily basis? Basic activities of everyday life may be grouped as follows: (a) Survival and health promotion, (b) Mobility and physical independence, (c) Orientation, (d) Communication and access to information, (e) Social integration and participation, (f) Economic security, (g) Self-determination, and the right to choose one’s own life style (2) What kinds of obstacles, and consequent coping problems, might people face while engaged in these basic activities? The environment contains numerous obstacles that may limit or prevent people with disabilities from undertaking the above-mentioned activities. In many cases these obstacles may also pose difficulty and risk to non-disabled people. (3) What – if any – changes are required in current planning practice to ensure that obstacles are not created? Issues such as access for all people should be fully and effectively incorporated throughout the planning and implementation process. (4) What kinds of additional support measures might be required to ensure that specific population groups are able to participate on the basis of equality in mainstream development? Despite careful and systematic analyses and planning, certain obstacles to full and effective participation by all may be created. In such cases specific support measures, e.g. assistive devices and personal attendants, may required to facilitate access to social life and development by all people. The figure I. 6 summarizes an approach to “planning for all people”. The first column presents the basic activities which everyone undertakes in daily life. The second column provides examples of people who may encounter obstacles in undertaking these basic activities. The third column lists areas for inclusion in planning and means (support services) to promote equalization of opportunities. FIGURE I. 6 PLANNING FOR ALL

|

It has been estimated that one person in ten has some form and degree of disability.31 This period ratio, however, leads to a serious underestimation if interpreted as the incidence of disability over the life cycle of an individual. The majority of people will have a shorter or longer personal experience with disability, particularly towards advancing age. Moreover, due to the ageing of population structures, the number of disabled people is expected to increase faster than the growth of the population as a whole.32 Taking into account the diverse functional limitations of people at the planning stage already decreases the need for special measures and the extra costs of accommodating the differences today and in the future.

A city for all

The Marjala suburb of the Finnish town of Joensuu was constructed to be barrier-free and accessible for all. There are no steps on the streets, the curbs are low but rough to accommodate both wheelchairs, baby prams and people who are visually impaired, streets are marked by contrasting colours, poles topped with raised symbols. Basically there are no housing units “for the disabled” but the housing units can flexibly be changed according to the special needs of the tenants. The idea was to build lifecycle homes that serve the family when the babies are small, when children go to school and still when the parents grow old and eventually need assistive devices. The project was awarded the golden prize of the European Union HELIOS programme in 1995.a

a Personal communication of Mrs. Pirkko

Kylanpaa, contact person for “A City for All”,

the Marjala Project, P.O. Box 59, 80101

JOENSUU Finland; E-mail : '; document.write( '<a '="" +="" path="" '\''="" prefix="" addy67831="" suffix="" attribs="">' ); document.write( addy_text67831 ); document.write( '<\/a>' ); //-->

2. THE ROLE OF THE MANUAL IN GLOBAL STRATEGIES TO PROMOTE “A SOCIETY FOR ALL”

In 1990 the United Nations General Assembly, in its resolution on disability policies and programmes issues, inter alia, invited member States to develop strategies towards a society for all and “requested the Secretary-General to shift the focus of the United Nations programme on disability from awareness-raising to action with the aim of achieving a society for all by the year 2010…”.33

Since that decision the international community, at the World Summit for Social Development in March 1995, committed itself to the goal of “human well-being for all” and to promote strategies that equalize opportunities for all people to participate in development.34

The manual seeks to contribute to international action to create favourable environments to achieve the objectives of “a society for all” by its focus on practical concepts and approaches to include social concerns in mainstream development.35

An inclusive society for all people

The concepts of “equalization of opportunities” and “a society for all” have been used by the disabled people’s community since the early 1970’s. Now these strategic concepts have gained wider currency and applicability, for instance in the “Copenhagen Declaration on Social Development” and “Programme of Action of the World Summit for Social Development”.a

“The aim of social integration is to create ‘a society for all’, in which every individual, each with rights and responsibilities, has an active role to play. Such an inclusive society must be based on respect for all human rights and fundamental freedoms, cultural and religious diversity, social justice and the special needs ofvulnerable and disadvantaged groups, democratic participation and the rule of law.”b

a Report of the World Summit for Social Development,

Copenhagen, 6-12 March 1995

(A/CONF.166/9), chap.I, resolution 1, annexes I and II.

b Ibid., para. 66.

With respect to inclusion of the disability dimension in social policies and development, selected strategic interventions and relevant international instruments of the United Nations are summarized below:

Long-term Strategy Level:

Long-term strategy to achieve a society for all – from awareness-raising to action36; and “Towards a society for all: long-term strategy to implement the World Programme of Action concerning Disabled Persons to the year 2000 and beyond”.37 The documents provide both a basis for design of umbrella approaches and a framework for mobilizing collaborative action at all levels – international, regional and national – to achieve the objectives a society for all by the year 2010.

National-level Policy Design:

Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities. 38 The document provides interested Governments with technical guidelines on the design of national disability options and related legislation and administrative guidance.

Planning Level:

The current document, The Disability Dimension in Development Action: Manual on Inclusive Planning, focuses on concepts, methods and procedures to reinforce disability issues in mainstream development and to further thereby achievement of the objectives of a society for all.39

Programme Level:

Programme Advisory Notes, and similar technical guidelines, on integrating disability issues into development cooperation activities of country programmes were identified by the Experts meeting at the mid-point of the Decade as important tools for formulation and coordiation of both national programmes and development

assistance, on request.40

Establishment and Development of Information Resources:

Development of a pilot Clearinghouse Data Base on Disability-related Information Resources (CLEAR) was initiated by United Nations in the light of a recommendation submitted by the Experts meeting at the mid-point of the Decade. The data base is currently under development on a variety platforms and contains, inter alia, data on selected successful examples of integrated policies, programmes and projects which contribute to furthering implementation of the World Programme of Action.

Programme / Project Implementation Level:

The General Assembly has recommended that consideration be given to initiating “spearhead” pilot projects in partnership with interested parties to assist Governments on request to further implement comprehensive integrated policy approaches to disability.41 Such projects could be organized as joint ventures

between governmental, intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations; and they should reflect bottom-up rather than the traditional expert-driven approaches.Figure I.7 summarizes graphically contents of a comprehensive strategy on a “society for all” together with examples of integrating activities and promotional instruments at the conceptual, policy and operational levels. The graphic summaryincludes examples of support services that could be provided on requested by compentent intergovernmental bodies and organizations.42

FIGURE I.7 OUTLINE OF A STRATEGY:

“TOWARDS A SOCIETY FOR ALL – FROM AWARENESS TO ACTION”

LEVEL I:

Long-term development objectives:

Strategic Priority: Empowerment of persons with disabilities

<a '="" +="" path="" '\''="" prefix="" addy67831="" suffix="" attribs="">

| Enhancing the well-being of persons with disabilities: | ||||

| Essentials of life | Full participation | Equality | Independence | Self-determination |

| Through ensuring the following societal prerequisites: | ||||

| Effective prevention | Rehabilitation for all in need | |||

| Fully accessible society | Adequate support services | |||

|

||||

LEVEL II:

Medium-term objectives:

Strategic Priority: Promoting Human Rights of persons with disabilities

|

|

Applicable to national disability policy design and evaluation | ||||

| • Human rights instruments of the United Nations • International action programmes: - Health for All - Education for All - etc. |

Standard Rules on Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities • ILO Conventions (for instance, rehabilitation) |

Specific medium-term goals and objectives for selected areas of national priority action for 1990’s related to the objectives of the society for all strategy |

LEVEL III:

Mechanisms:

Strategic Priority: Involving organizations of persons with disabilities in mainstream development

| Mainstreaming and social integration |

Partnership and full involvement |

Coordination, Advocacy and enforcement | Medium-term planning | Mobilization from awareness to action | Resources pooling |

|

|||||

LEVEL IV:

National level action:

Strategic Priority: Inclusive policy approaches

| Expected results • Increased integration in national policies, programmes and projects • Primary health care (PHC), and related integrated prevention measures • Community-referenced and integrated rehabilitation services • National disability legislation • Functional organizations of disabled persons and related bodies • Improvements in accessibility • Improved prerequisites for independdent living • Improved opportunities for income generating opportunities • Appropriate social services |

Action for implementation • Comprehensive review of policies • National forum to design a policy document • Design a medium-term action plan • Establish coordination and monitoring mechanisms • Support organizations of disabled people • Integrate disability into national policies for socioeconomic development • Integrate disability issues into technical cooperation activitie |

|

|

International support for programme countries:

Strategic Priority: Sustained development from the social perspective

| • Maintain high-level political support • Strengthen the United Nations’ role • Focus on regional approaches and “South-South” cooperation |

• Increase technical cooperation • Integrate into mainstream activities • Improve division of labour, coordination and partnership • Initiate joint pilot projects |

• Design a feasible inclusive policy • Develop co-ordinated planning and co-operation fora • Develop an effective monitoring and follow-up systems |

|

||

Role of the United Nations focal point on disability:

Strategic Priority: Building capacities for integrated strategies, policies and programmes for a society for all

| • Formulate standards and guidelines (e.g. Standard Rules) • Formulate policy options (e.g. Long-term strategy) • Draft technical manuals on methods and procedures • Organize training and technical exchanges on priority topics |

• Establish and develop information networks • Promote and support cooperative networks for consultations on coordination of action (e.g. use United Nations system interagency mechanisms to promote increased joint action, partnership and alliances) |

• Promote awareness and understanding of issues and trends among specialized public,(Governments, NGOs, academic community and private sector) • Identify, review and assess selected experience with a view to documenting “good practice” • Mobilize support for policy and programme developments • Provide on request advice and assistance in key knowledge areas |

NOTES: Unit I

- United Nations General Assembly resolution 46/96.

- United Nations document A/37/351/Add.l and Corr.l, annex, sect. VIII, recommendation I (IV).

- United Nations General Assembly resolution 47/3.

- Ibid., para 173.

- United Nations General Assembly resolution 42/58, para.5.

- Op. cit., para 6, and General Assembly resolutions 43/98 and 44/70.

- United Nations, “Report of the expert group meeting on a long-term strategy to further the implementation of the World Programme of Action concerning Disabled Persons to the year 2000 and beyond (Vancouver, 25-29 April 1992) note by the Secretary-General” (E/CN.5/1993/4), annex, para. 54.

- Ibid., para. 62.

- Ibid., para. 66(b).

- United Nations document A/47/415 and Corr. l.

- United Nations General Assembly resolution 47/88.

- United Nations, Commission on Human Rights, “Human rights and disability, final report prepared by Mr. Leanardo Despoy, Special Rapporteur of the Commission on Human Rights” (E/CN.4/1991/31). See also Einar Helander, “Prejudice and disability: an introduction to community-based rehabilitation” (New York, United Nations Development Programme, 1992).

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), “Alternatives to institutional care; report of UNICEF-ISCA Workshop for Central and Eastern Europe (Riga, Latvia, 29 January – 2 February 1995)” (Ronald Wiman, rapporteur), published for UNICEF by National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health (STAKES), Helsinki, 1995.

- United Nations Report of the World Summit for Social Development, A/CONF. 166/9, chap. I, resolution I, annex II.

- See discussion in Ronald Wiman, “From labelling to enabling; development of conceptual instruments for understanding people’s coping problems”, Proceedings of the scientific colloquium on functional limitations and their consequences (Montreal, Canada, 18-20 November 1992), in Elargir les horizons; perspectives scientifc sur I’integration sociale; Editions multimondes, publi, en coeditions avec L’Office des personnes handicapées du Québec (Québec, IBIS Press, 1994).

- World Health Organization (WHO), International classifcation of impairments, disabilities and handicaps (Geneva 1980), pp.27-29; and World Programme of Action concerning Disabled Persons, para. 6.

- Status of Disabled Persons Secretariat, Department of the Secretary of State of Canada, A Way with words; guidelines and appropriate terminology for the portrayal of persons with disabilities [1990]. Note: in 1993 the functions of the Status of Disabled Persons Secretariat, Department of the Secretary of State of Canada were assumed by the Department of Canadian Heritage.

- Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities, United Nations General Assembly resolution 48/96, annex.

- Ibid., annex, para. 24.

- United Nations General Assembly resolution 217 A (III).

- United Nations, World Programme of Action concerning Disabled Persons, DPI/933/Rev.l. August 1992, para. 25.

- Ronald Wiman, Towards an integrated theory of help, pub. 2/1990 (Helsinki, National Board of Social Welfare, 1990).

- Standard Rules..., annex, para. 23.

- Ibid., rules 3 and 4.

- Ronald Wiman (1990), op. cit.; and Ronald Wiman, “The social dimension of sustainable development – a society for all”, Dialogi; Journal of the National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health, English supp. 4b (1994) pp. 11 – 14.

- Standard Rules..., annex, para.22; and World Programme of Action concerning Disabled Persons...., paras. 50-55.

- Report of the World Summit for Social Development..., annex I, para. 1.

- Ronald Wiman (1990), op. cit.

- Ronald Wiman (1994), loc. cit.

- United Nations, Department of Public Information Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities, pub. DPI 1476 (New York, May 1994).

- Based upon data compiled by the United Nations on 55 countries during the 1980s the percentage of the population that is disabled varies from 0.2 to 20.9 per cent of surveyed populations in Disability Statistics Compendium, Statistics on Population Groups, Series Y, No. 4 (United Nations publication, Sales No. .90.XVII.17), p. 25-27. The Compendium notes that the wide range of disability rates reflects not only variations in the level of disability but a high degree of variability in strategies for measurement of disability among countries (p. 27).

- See, for example, Averting the old age crisis; policies to protect the old and promote growth, a World Bank Policy Research Report (New York, Oxford University Press, 1994).

- United Nations General Assembly, resolution 45/91.

- Report of the World Summit for Social Development.., chap. I, resolution 1, annex I, “Copenhagen Declaration on Social Development”.

- Ibid., Commitments 2, 4 and 8 in particular.

- United Nations General Assembly resolution 45/91.

- United Nations document A/49/435, annex. General Assembly resolution 49/153, inter alia, calls upon Governments to “take into account the elements suggested in the Long-term Strategy...”.

- General Assembly resolution 48/96, annex.

- The manual has been prepared in the light of recommendations submitted at the Global meeting of experts to review the implementation of the World Programme of Action concerning Disabled Persons at the mid-point of the United Nations Decade of Disabled Persons (Stockholm, 17-22 August 1987): United Nations document A/42/561, General Assembly resolution 42/58.

- Ibid.,General Assembly resolution 47/88 requested the Secretary-General, inter alia, to integrate disability issues into programmes and projects of the specialized agencies “on a broader scale and with a higher priority”. The United Nations Development Programme recently has issued intersectoral “Guidelines for Programme Support Document” (New York, November 1993) for the analysis and planning of its pre-investment assistance.

- United Nations General Assembly resolution 47/88.

- United Nations document E/CN.5/1993/4; and Bengt Lindqvist, “Towards a society for all – from awareness to action; a draft long-term strategy to further implementation of the World Programme of Action concerning Disabled Persons to the year 2000 and beyond”, unpublished paper (12 November 1992).

| II UNIT TWO: GUIDANCE FOR THE DESIGN OF INCLUSIVE POLICIES AND PROGRAMMES |

A. INCLUSIVE NATIONAL POLICIES

1. ENABLING ALL PEOPLE TO LIVE MEANINGFUL LIVES

All poor and vulnerable groups in society share the situation of being excluded from access to opportunities and choices available to the rest of society. Equal opportunity policies that adhere to Universal Human Rights and the enabling approach to social services are the cornerstones of strategies that focus on the development of human capacities. This approach makes it possible to address the diverse problems of people within an inclusive framework and through an integrated rather than a sectoral service delivery system

“A society for the few”

About one billion people are living in absolute poverty with barely enough food and shelter to survive.a The Report of the World Summit for Social Development states that “eradication of poverty cannot be accomplished through anti-poverty programmes alone”. “Poverty is inseparably linked to lack of control over resources, including land, skills, knowledge, capital and social connections. Without those resources, people are easily neglected by policy makers and have limited access to institutions, markets, employment and public services.”(WSSD para 23) The poorest people are left without hope and human dignity due to the inequalities created by a societies that benefit a small group of the privileged, only.

a United Nations Report of the World Summit for Social Development, A/CONF.166/9, Annex I, para 18–19, p.41

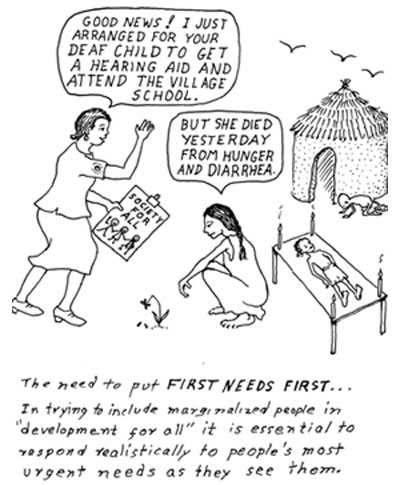

First needs must be addressed first. The fundamental aspiration of all people is, however, not bare survival. Also poor people strive for more.

FIGURE II. 1 FIRST NEEDS FIRST

|

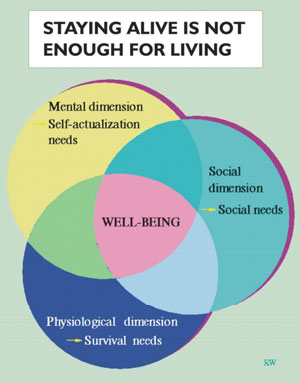

All people are equal in human nature. The physiological, social and mental dimensions of a living human being are inseparable. None of these exists alone. All people have the same fundamental needs. Survival needs must be met to stay alive. Survival needs are, however, narrow and limited and should not be considered identical to the “basic human needs”. The fundamental essence of human life is, after all, to strive towards a meaningful life. Meaning in life is created by social interaction towards the realization of one’s human potential. The self-actualization needs are limitless and they get their expression in people’s aspirations towards “a life of their own”, independence, selfdetermination and creativity through full and equal membership of the family, the community and society. “Well-being” is, therefore, a product of all these aspects of life. Therefore, adding to one cannot compensate the lack of another.1

FIGURE II. 2: WHAT IS WELL-BEING?

|

The hierarchy of human needs is usually drawn as a pyramid where survival needs (physiological needs) form a broad base and self-actualization needs (mental and spiritual) presented at the top as the tip of an iceberg. This conceptualization is misleading and is poor a tool for policymaking just as a wrong map would be for orientation in a big city. Survival needs are limited. Social needs can hardly be separated from the essence of human existence itself. Mental and spiritual needs and capacities are limitless and reflect the ultimate objectives of human existence.

FIGURE II. 3 THE HIERARCHY OF HUMAN NEEDS

– THE RIGHT SIDE UP:

One does not live to eat; one eats to live.

|

Poverty and insecurity deprive people of all these aspects of life at the same time. Consequently, poverty eradication calls for a broadening of the arenas of life of those who are poor by simultaneously enabling people to have better access to and better control over the essentials of life, the social and power relations and the development of their own person.

Well fed – but utterly poor children

In many of the former centrally planned eastern European countries now making the transition to market economies, it was a standard practice to place children with disabilities in large state institutions. Disabled children were often abandoned by their parents. They became “social orphans” of living parents. The practice was encouraged by medical and social welfare professionals. Thousands of disabled children lived in those institutions, rather well-fed and clothed. But never in their lives did they own a single personal belonging. They never had a single steady personal relation with an adult. They never had any hope for a future outside the institution that provided for their “basic needs”.a

Since the international community became involved at the beginning of the 1990’s, an enormous improvement in the lives of children has been achieved within a few years with the help of international organizations, including UNICEF. One of the main reasons for this success was the adherence to the Convention on the Rights of the Child of the Child which stated that “State Parties recognize that a mentally or physically disabled child should enjoy a full and decent life, in conditions which ensure dignity, promote self-reliance, and facilitate the child’s active participation in the community.” Article 23, para 2 b – Keeping children only alive is never enough.

a UNICEF “Alternatives to Institutional Child Care”, Report of the Workshop for Eastern and Western Europe, convened by UNICEF and ISCA, in Riga, Latvia 29 January - 2 February, Rapporteur Ronald Wiman, Published for UNICEF by STAKES, Helsinki 1995, pp. 6-8.

b“The Rights of the Child”, Human Rights Fact Sheet No. 10, Centre for Human Rights, United Nations, Geneva, 1992.

The realization that people, by their very nature, are active agents who want and are capable of being in charge of their lives rather than being merely passive bjects of care, has led to a new understanding about social development.

“Human beings are at the centre of concerns for sustainable development. They are entitled to a healthy and productive life in harmony with nature.”2 This first principle of “The Rio Declaration on Environment and Development” and the priority goal of “well-being for all” of the World Summit for Social Develoment call for the reconsidering of national development policies. A major change of focus is needed. While society has the duty to ensure the availability of the essentials of life for all, it must also simultaneously enable all people to fully participate in society and pursue their own aspirations and diverse goals as full and responsible

members of society. A major reallocation of access to and command over material resources, social networks and power structures on the world scale and within nations is needed.3 This would involve the shifting of priorities beyond the minimum needs of marginalized people and the corresponding reallocation of opportunities for meaningful participation and self-actualization. Social development is a process of enlarging the choices for all people. 4

2. ADDRESSING DISABILITY IN AN INCLUSIVE POLICY STATEMENT

The enabling approach was already reflected, if not as clearly and universally as today, in the World Programme of Action concerning Disabled Persons in 1982 which introduced the concept of equalization of opportunities and equal access to society.

“Matters concerning disabled persons should be treated within the appropriate general context and not separately. Each ministry or other body within the public or private sector responsible for, or working within, a specific sector should be responsible for those matters related to disabled persons that fall within its area of competence .” (WPA para 89)

The Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities, adopted in 1993 reaffirm strongly the principles of inclusive policies, plans and activities on:

“The needs and concerns of persons with disabilities should be incorporated into general development plans and not be treated separately.” (SR 14.4).

In order to ensure the applicability of the equal opportunity principle to all situations and all people, it is desirable for the commitment to be expressed at highest possible level.

Non-discrimination of disabled people as a Constitutional right

The Constitution of the Republic of Uganda, adopted and enacted by the Constituent Assembly on 22 September 1995 and promulgated on 8 October 1995 recognizes the rights of disabled people. Chapter four, “Protection and Promotion of Fundamental and Other Human Rights and Freedoms” states:

- “Persons with disability have a right to respect and human dignity and the State shall take appropriate measures to ensure that they realize their full mental and physical potential”;

- “Parliament shall enact laws appropriate for the protection of persons with disabilities”.

Under Cultural Objectives the status of Sign Language is recognized: (the State shall) ”promote the development of a Sign Language for the Deaf.” a

In Finland, protection against discrimination on the basis of disabilities, or other personal characteristics, and the right to use Sign Language are constitutionally guaranteed (as revised August 1995).

Paragraph # 5 states: “All persons shall be equal before the law.”

“No distinction shall be made without acceptable reason on the basis of sex, age, origin, language, religion, conviction, opinion, health, disability or for the other reason related to person.

Children shall be treated equally as individuals, and they shall be allowed to influence matters affecting them according to their level of maturity.”

Paragraph # 14 states: “The rights of those using Sign Language or of those who are in need of interpretation or translation because of a disability shall be secured by Act of Parliament”.b

For instance in Canada and Germany, the rights of disabled people are recognized in their respective constitutions. Some countries have adopted comprehensive antidiscrimination legislation, such as the“Americans with Disabilities Act” in the United States of America.

a World Federation of the Deaf

b Scheinin, Martin Incorporation and Implementation of Human Rights in Finland, p. 292, article in Scheinin Martin (ed.): Human Rights in the Nordic and Baltic Countries, Kluwer Law International, Boston 1996.

In the framework of a general commitment to equal opportunities, the specific statement of intent and priorities concerning people with disabilities should focus on their empowerment, that is, on enabling them to take charge of their lives on equal terms with other people. This calls for ensuring reasonable access for all to the basic activities of life by which people provide for their essentials of life, to equally and fully participate in society, to gain independence and exercise their right to self-determination.

However, it is not possible for people who have disabilities to participate in such basic activities on equal grounds with others without the following additional prerequisites5:

- the dignity and fundamental rights and freedoms of people with disabilities must be recognized;

- prevention of disabling conditions, including early intervention in case of illness, must be accorded appropriate priority;

- rehabilitation must be available for those who need it;

- accessibility must be reasonable;

- auxiliary support services, including assistive devices, tailored environments, and support to families must be made available when needed.

In cases where a person with a disability needs to be represented by another person, these prerequisites should be made available through such persons, for example, parents of disabled children or eligible care-takers of people with serious intellectual disabilities.6

All five prerequisites should be addressed simultaneously, not just one or a few (see also Unit IV).

FIGURE II.4. A MISSION STATEMENT FOR AN INCLUSIVE NATIONAL POLICY TOWARDS DISABLED PEOPLE

| The strategic mission: Towards an Inclusive Society for All People Disability policy objective: Enhancing the dignity, well-being and empowerment of disabled people, By enabling them to achieve: • The essentials of life • Equality and Full Participation • Independence and Self-determination Through ensuring the following additional prerequisites: • RECOGNITION OF RIGHTS • PREVENTION OF CAUSES • REHABILITATION • UNIVERSAL ACCESS • SUPPORT SERVICES |

| These empowering prerequisites can be ensured and organized in various ways. As it is not possible to cater for the needs of the majority of the disabled people by focusing on labour and capital-intensive, specialist-driven approaches, there is an urgent need to turn away from the social welfare driven care approach towards enablement. Empowerment leads to the full use of human potential and to sustainable development “If you wish to harvest once just sow, If you wish to harvest ten-fold plant a tree, If you wish to harvest one hundred-fold educate people.”(Lao Tse) 3. STANDARD RULES ON THE EQUALIZATION OF OPPORTUNITIES FOR DISABLED PERSONS The most recent international guidelines for the formulation of national disability policy are the Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Disabled Persons. The Rules comprise 22 policy principles covering various sectors. Under each of the principles there is a set of policy options on how to implement the principle. The Standard Rules are easy to apply in different national circumstances. They provide a basic structure and guide for inclusive national policies on disability. The rules emphasize the integration of disability issues into all relevant policies, (“mainstreaming”), rather than treatingthem in isolation or separately. FIGURE II. 5 STANDARD RULES ON THE EQUALIZATION OF OPPORTUNITIES FOR PERSONS WITH DISABILITY

|

| International standards are applicable in all countries In several countries the Standard Rules currently serve as a reference for the revision of national disability policies and legislative reforms. In Estonia the Standard Rules have been adapted to constitute the national disability policy. In Finland national disability policy was revised by the National Disability Council. The current situation was reflected and evaluated against each of the Rules and a corresponding proposal for action was made.a a “Kohti yhteiskuntaa kaikille”, Valtakunnallinen vammaisneuvosto 1995, (Towards a Society for All, National Disability Council, Helsinki, Finland. Available in Finnish, Swedish and English). 4. TEN STEPS TOWARD A NATIONAL DISABILITY POLICY The direct application of the Standard Rules may be called a “normative approach” to the design of national policies. An alternative is to use a “developmental approach” that involves all the relevant actors already at the design stage. With such “bottom-up” involvement people learn by doing. It represents the first step in the implementation of the resulting policy. International standards can, naturally, also be used as reference material in such a process. A developmental step-by-step approach to designing a national disability policy may look as follows7: -> Step 1: Establish a task force An initial task force should include a group of people who are able to work together and have a fresh insight into development. At this stage, the membership of the group need not necessarily be representative but it should include participants from several relevant organizations, at least from disabled people’s organizations and key government ministries or agencies. -> Step 2: Design an initial policy statement The task force should first formulate an attractive and up-to-date draft policy statement, or mission statement, on the empowerment of people with disabilities. The purpose is to table crucial issues, whether the solutions are considered to be immediately feasible or not. At this stage, the development objectives must be set in the right direction. -> Step 3: Make a situation analysis The current disability situation, the status, living conditions of and opportunities for disabled people, the existing policies, the programmes and plans are reflected against the new mission and the development objectives. -> Step 4: Stage an awareness-raising event In order to draw the attention of the media, generate public discussion and mobilize people with disabilities and their organizations, a visible event should be staged. -> Step 5: Arrange a national forum The purpose of a national forum is to involve and commit all the relevant agencies and to receive detailed inputs to further discussion. A broad based coalition to complement or replace the initial task force for further work should result. -> Step 6: Arrange a consultations round Initiate a process of wide consultation with the full involvement of all relevant partners, especially organizations of people with disabilities, in order to design a national disability policy that addresses the needs and concerns of persons with disabilities, as well as the political and economic realities of the country. Seek inputs to the development of a national action plan from: – all ministries at all administrative levels of Government; – organizations of people with disabilities; – other non-governmental and community- based organizations; – representatives of regional and grassroots/ municipal organizations. -> Step 7: Draft a policy paper While setting the situation in its historical context, the policy paper should be based on the development objectives derived and adapted from the current international consensus, such as the Standard Rules. The paper should state the immediate urgent needs, medium-term targets and long-term objectives. Furthermore, it should select the priorities, make a feasibility study and design a step-by-step plan of action for reaching each of them. It is vital to include measures and mechanisms that have long-term strategic potential, such as the establishing and/or strengthening of a national coordination mechanism, and supporting the self-help organizations of disabled persons to play an effective role in the development of national policies and programmes. That support may include resource allocations and a milieu conducive to governmental/ non-governmental organization cooperation. -> Step 8: Establish a regular monitoring system The policy paper should specify and identify resources, appropriate institutional arrangements and the distribution of responsibilities for the implementation of the plan. In order to make all relevant agencies accountable, the implementation should be monitored by a task force, National Coordinating Committee or a coalition of disabled people’s organizations. -> Step 9: Set benchmark years for revision The policy should be kept alive. Stick to principles rather than to the letter. Let the implementation arrangements live and respond to the local contexts. Arrange a revision workshop or forum at regular intervals (2–4 years). -> Step 10: Expand the participation of disabled people in all aspects of life Get to work to implement the policy at all levels. Aim at bringing in and including disability concerns in all aspects of society. On all occasions promote the participation of people with disabilities in national policies, programmes and projects for economic and social development. Examine also international cooperation policies, programmes and projects, with a view to promoting the integration of disability concerns and the participation of people with disabilities therein. This will help to keep disability concerns on the high political agenda. A long journey starts with the first step– in the right direction In Namibia, in 1991 a national workshop was conducted with the main objective of identifying the major needs of people with disabilities. The workshop recommended the following steps, which are now in the process of implementation: (1) Cabinet adoption of a national plan for the integration of disabled people in the rest of society. (2) An awareness campaign for communities to realize the needs and equal opportunities for disabled people. (3) Drafting of disability legislation to protect the rights of disabled people. Done so far (1994): (1) The report of the national workshop was taken by the cabinet as a working document for the Division for Rehabilitation. (2) Awareness campaigns were conducted in 1992–1993 to coincide with the End of the Decade of Disabled Persons activities. (3) A national workshop on legislation was held and a six-member committee was elected to draft the legislation. The committee consisted of the Ministry of Lands, Resettlement and Rehabilitation, the Ministry of Basic Education, the Ministry of Justice and disability organizations a a United Nations Consultative Expert Meetingon Integration and Disability Issues in Development Cooperation Activities, Vienna, 29 May - 2 June 1995 (Vienna EGM) and International Round Table on Disability, Third Meeting, Joensuu. Updated information is available in the SFA network in the Internet (http://www.stakes.fi/sfa) 5. THE ROLE OF SOCIAL SERVICES AND SOCIAL SECURITY Disability issues should not be considered as a matter for social welfare, social care or charity but rather as a central issue of human rights and social development. While the ultimate responsibility for the human rights of disabled people remains with the State, the primary responsibility for enabling people with disabilities to live a meaningful life stays in the community where they live. 5.1 Who are the actors on the scene? People are by nature active, socially and morally conscious, goal-oriented agents of their own lives. Well-being cannot, therefore, be given to people from outside. People themselves produce their wellbeing, provided that the prerequisites are available. Governments have the responsibility to ensure that such prerequisites are available for all.8 Individuals obtain the goods and services necessary for their well-being by interacting with other members of the family or household they belong to – by exchanging goods and services from the various “markets”. The markets consist not only of the profit-making private sector (business) but also the public sector and the non-profit NGO sector. Furthermore, there is the “community” where people live. A “community” consists of networks of physically or socially close people. These people are members of the business community, the grassroots employees of the public sector and the more or less organized networks of people and families, the so-called non-profit NGOs. And naturally, individual families and their members are themselves part of the community. Therefore a community belongs neither to the “public” nor to the “private” (profit or non-profit) sector. The community includes and involves all the people. Each of these agents has a role to play. We can illustrate the “stage” where these agents act with the help of a tetrahedron (Figure 6). Each agent (or actor) is located in one of the four corners. The exchange of goods and services takes place in the space inside this tetrahedron. This threedimensional “stage” we call “the welfare market”. The well-being of people is a mix of various inputs derived through interaction with all these actors.9 The integration of disability concerns and the participation of people with disabilities in the mainstream of development policies and programmes should not be left to any one sector alone. It requires the cooperation of:

|